Before shelving a book in our collection, no matter the review nor recommendation, here at the Takoma Park MD Library we always run a ‘panel check’ on every graphic novel we add.

This means I read a great many comics of course, the point here is to confirm where a book belongs in our collection, and in our children’s section to avoid any upsetting surprises for patrons hunting for an appropriate book for their kid. Adult language, realistic violence, sexually charged situations, mature topics– these are all reasons why a book may step up the ladder to the next higher age category. (See promotion criteria at the bottom of this article).

Occasionally we get ambushed by a wolf-in-sheep’s-clothing and buy a book intended for a young audience, but discover a single panel of art that bumps it to a higher category. Kid-to-grown-up ‘booby-trapped’ books are especially upsetting when an otherwise great story, appropriate for all ages, is derailed by unfortunate racial stereotypes or caricatures.

Here is a smattering of otherwise excellent books that are tainted by their own prejudices.

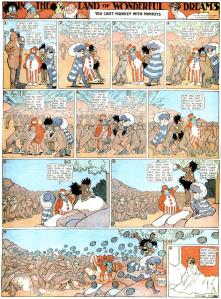

The incomparable Windsor Mckay’s visionary Little Nemo in Slumberland has so many beautiful sequences I would love to share with the audience of our monthly Comics Jam read-aloud, but it is too worm-eaten with the racial insensitivity of the early 1900’s to display without sophisticated discussion. The emotionally precocious kids in our Banned Books Club might enjoy this conversation, but I can’t see that working for our afterschool crowd, who prefer their comics loud funny exciting and mostly unfiltered by extraneous chit-chat.

McKay’s brilliance has had a trickle-down effect on many cartoonists who were clearly influenced by his work, or who outright plagiarized his stories for their own works, and were in turn copied and repeated elsewhere. Stereotypes are commonly held images of a group of people, and I suspect that the genius of Mr McKay helped to illustrate and animate the initial images of Africans, Asians, or Native Americans in the heads of many of his readers, including a legion of artists who emulate his talents.

One such artist was the Belgian cartoonist Herge’, author of the Tintin series.

The Adventures of Jo, Zette, and Jocko: The Secret Ray, by Herge.

Herge’s editor approached him with a suggestion for a new series that would appeal to children. Tintin is fine and all, but he has no family that loves him, no mother or father or obvious means of support, and is therefore less believable to children. Thus was born the Adventures of Jo, Zette, and Jocko.

Reading reviews I thought: ‘Here’s a great idea, the story of a brother, sister and their pet chimp who accidentally stumble into adventure, then survive by pluck and verve. Written and illustrated by the author of Tintin? Order me a copy quick! Why haven’t I heard of this?’

Here’s why: by page 58 the siblings have been captured by a cannibal tribe on a desert island drawn in minstrel-show blackface, speaking in an ‘ooga-booga’ pidgin language. The siblings manage to survive the encounter by impressing the natives with their superior technology and of course then are worshiped as gods. Naturally.

Granted, anyone who knows a little about Herge has been inoculated with the idea that, especially early in his career, the creator of that intrepid boy reporter suffered from the self-important and ignorant colonialist worldview of many his readers in 1930′ s Belgium. Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, Tintin in the Congo, Tintin in the Americas all betray a narrow understanding of the world. He later came to regret many of his earlier works, claiming that in par they were written to please the sensibilities of his editors.

Still, flipping the page to stumble into these panels here brought me to a halt akin to riding a tenspeed into a guardrail. Stunning. I asked myself: ‘is it salvageable? Can we still keep it on the kid side? Maybe in the Young Adult collection?’

In this case the answer was ‘no’. If there were a single panel or off-color joke, maybe it could be glossed over or looked at as an instance of a teachable moment. Instead here Herge reprises a scene from Tintin in the Congo with childish and stupid natives being driven away by the children’s clever pet monkey and a fusillade of coconuts (in a scene lifted directly from various panels of Little Nemo) — whereupon the siblings all retreat to their armored tank and threaten the primitives with it’s advanced weaponry. European force of arms wins once again.

Now there are books that we do keep in the children’s collection despite stereotypical and potentially insulting images. Consider fellow Belgian comic ‘Asterix’ which remains happily on the kid side. There, various ethnic types are skewered by the pen of Rene Goscinny– and if your ancestors have not yet been granted the same treatment, you need but read a few volumes further. The difference between the two being that Asterix is rendered in absurd fashion, lampooning all and sundry equally — its primary protagonists being a big bellied gluttonous boob and a pint-sized scrapper with a Gallic schozz.

Much may be forgiven if a book manages the alchemy of humor, or truth. In the case of Jo, Zette and Jocko, Herge managed none of these, instead relying on a cliche based on disdain and ignorance — all the more frustrating considering the careful research he gave to many of his adventure stories, learning background details about the country terrain or culture in order to render his striking images. To be fair Herge learned a great deal as he grew in skill and maturity. His later books display a greater appreciation for the settings in which he based his stories, and those of us who read them many decades later can still appreciate the humor and draftsmanship.

But here, in this juvenile work, Jo, Zette, and their monkey were promoted to the Adult side as a curiosity for those who want to read the entire Herge oeuvre. Book two in this series had none of those same images and still sits the shelf in the kids room, so people who pick up that one may track down the earlier volume, but they’ll have a moment to wonder why the book landed on the children’s side.

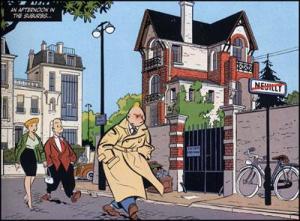

Spirou and Fantasio, in New York. by Tome and Janry

Contemporary of Tintin, Spirou is a long-running French language comic strip with many of the same themes and sensibilities of the former. It is illustrated in a more cartoony style than Tintin, akin to Asterix, though the storylines follow the adventures of a boy reporter on his quest to chase down a good story (more than solving mysteries in particular).

Humor tends towards broad slapstick, and like Asterix the lack of sophistication makes any ethnic insensitivity easier to gloss over. Our first volume of the series (Spirou and Fantasio: Adventure Down Under) was added to our all-ages collection. Volume two however (Spirou and Fantasio In New York) required a re-assessment.

In this late volume the two become embroiled in a comedy of errors involving feuding gangs in Manhattan: a Chinatown tong against Sicilian mafia. Story is fast paced, humor is occasionally witty, but while light in tone the characterizations of all ethnic types are pretty distasteful. “Ah so” Chinese and “deze, dis, doze” Italian accents clot the dialogue, and the art isn’t quite funny enough to pull it out of the muck. We bumped the book to the Young Adult side, and it has subsequently disappeared, will likely not be replaced.

Chaland Anthology Volume #1: Freddy Lombard, by Yves Chaland.

The three stories of this collection showcase Chaland’s best known character: Freddy Lombard, a Tintin clone, albeit with a darker more cynical sensibility. The art is drawn in a similar ligne clare style as Herge’s famous character — cartoony characters, realistically detailed backgrounds, vivid solid colors, though the artwork allows heavier inkwork in outlines and shadow. Similarly the the stories are darker, more comfortable more moral ambiguity than Herge’s earnest boy reporter.

Due to mild nudity, adult situations etc this book was likely destined for our Adult collection anyway, but the second story of book one would have tipped it over the edge regardless.

In the first story ‘The Will of Godfrey of Bouilllon’, Freddy Lomabrd and his friends Sweep and Gina suffer car trouble in the rain and are given shelter in a mysterious castle.

The master of the manor inveigles them into his quest to find the secrets of his ancestor, a Crusader knight. The story bounces between a dream sequence or vision of the past and the protagonists modern day quest for this treasure in the catacombs beneath the castle. Noir lighting, clever panel composition, terse witty dialogue, plot twists — so far so good.

In the second story The Elephant’s Graveyard we bump into deliberately overt racism and self-satisfied colonialism undimmed by Tintin’s earnest naivete. In a quest for a rare glass photonegative supposedly taken by the explorer David Livingstone, Freddy and his pals find themselves on a flight to Africa. There, in a bar they meet a contact who purports to have a map that will send them to find the tribe that has possession of the plate. The brusque and ill-tempered Sweep causes a bar fight when he shouts a racial epithet at the African proprietor of the saloon.

Here Chaland purposely lampoons the tired tropes of primitive African tribesmen cowed by the technology and force of personality of the brash Europeans, etc, etc. Decades after Herge, Chaland clearly recognizes that his protagonists are greedy, exploitative, and lacking in good graces– an ironic comment on Tintin’s oblivious colonialist chauvinism. Which in and of itself makes the book more interesting, if not appropriate for a younger audience. Irony requires sophistication to appreciate. However even drawn with a knowing wink, the depictions of African tribesmen as savage barbarians is (deliberately) offensive.

Anyway, these books are worth checking out whether or not you wish to read them as a comment on Tintin or as standalone works. The art is remarkable, atmospheric, funny, dramatic by turns. Recommended for sophisticated comics fans. They don’t work however as a proxy continuation of the Tintin series, they are more mature than that.

————–

In brief, our promotion criteria is as follows:

- All ages or ‘comics’ collection: Cartoony violence okay. Cartoony romance, maybe smooching a la Archie comics.

- Young adult collection: Realistic violence okay, not gore. Light gunplay. An occasional cuss word. More nuanced romance, maybe sexually charged situations or excessively bulgy heroes in skintight spandex, but not overt nudity etc. Socially divisive concepts okay (racism, etc) if treated carefully.

- Adult collection: Anything else. Nudity, blood and guts, racially or ethnically divisive work or adult situations gvien starker treatment.